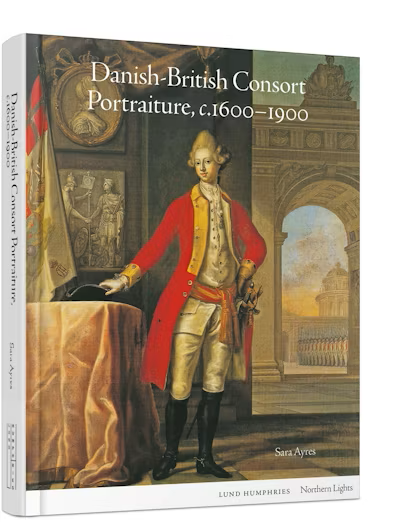

The title of this superbly illustrated book ostensibly indicates an overview of a specific group of royal portraits, produced over the course of three hundred years. An unusual focus on consorts who united the Danish and British royal families through marriage reveals the deep bonds between European dynasties, but also presents exemplary models for the author’s argument across otherwise broad and unmanageable periods of time. The book remains disciplined and centred, while at the same time offering a variety of evidence and new readings to make it a compelling and authoritative contribution to art history and visual culture. The chosen cover image, if unfamiliar to the reader, is assumed to represent one of these royal individuals in eighteenth-century military costume and with all the expected accoutrements of assertive might and power. However, it is soon revealed to encapsulate the far more complex narrative of the book. It subverts our expectations and challenges us to reassess what a portrait can tell us.

The 1770 portrait by Peder Als shows Caroline Matilda of Great Britain (1751–1775), the daughter of Frederick, Prince of Wales and Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, who was married to King Christian VII of Denmark. She wears the uniform of the Life Guards, with red coat, sash and spurs, and sword at her side, about to take her tricorn hat from the table and to stride out through an arched doorway to inspect a line of soldiers drawn to attention in the courtyard. Her story forms chapter four of the book. By then, the reader has followed the writer’s close readings of three other consort portraits and traced the postures, settings and iconography which connect them to tell a history of transformation in the art of embodying the royal image (p. 10). The portrayal of rank shifted into one based exclusively on gender, a shift which affects our ability to understand and interpret a portrait even today. The argument is original and intriguing, underscored by research references drawn from a broad range of visual culture and historical sources, in particular Walter Benjamin’s writings on the work of art in an age of technological reproducibility. The argument relies on detailed observation to find new connections. Of the five Danish royal consort subjects of this study, only one, Prince George of Denmark (1653–1708), is male, but the book aims to explore how the royal image “rhetorically incorporated the most functional, symbolic qualities of maleness and femaleness” (p.22). It centres on uncovering the “complex palimpsest” of royal portraiture as embodiment, centring on the 1617 Paul van Somer portrait of Anne of Denmark (Royal Collection Trust) as its starting point.

Anne’s full-length portrait incorporates elements of the traditional male hunting portrait, the horse, dogs and distant view of a royal palace and park, as part of her self-fashioning. It was importantly designed to “instruct and nurture” (p.44) her son Charles in the noble and princely arts necessary for kingship. Charles I’s dismounted equestrian portrait by Anthony van Dyck, dated to c.1635, can be construed as a pendant. The crooked elbow which features in these and later royal portraits is an important sign derived from emblem book symbols of female perfection. When added to examples of extended elbows in male portraits suggesting greater male heat and virility, a feature of the ancient four humours medical theory, it is clear that there was more gender fluidity and layered meaning in the royal portrait than we might have realised.

The book explores the construction of royal embodiment and its image through the physical nature of the medium. The discussion on Prince George of Denmark centres on his youthful Grand Tour which included England on its itinerary, and the shaping of a cultured and refined royal figure. The wax medium used for the clothed and wigged waxwork of the young prince by Antoine Benoist (undated), now in Rosenborg Palace, Copenhagen, indicates the pliable mind of the prince as he was prepared for a role of power. The advances in scientific and Cartesian methodology, while essential elements of a modern royal education, changed the nature of royal embodiment. Louisa (1724–1751), daughter of George II, married Crown Prince Frederick V of Denmark-Norway. Her death during a late stage in pregnancy was followed by an autopsy which her doctors described in detail, changing the sacral body into a pathological case study. As the author notes,“The artisanal epistemology that had been the province of the consort and the artist as they together crafted the contours of the royal body as a work of art now became the property of the man of medical sciences” (p.80). The work of the anatomist reinforced the changing balance of power and the female body was laid open to a newly authorised male gaze.

The final two chapters consolidate the narrative of change. The author offers a new interpretation of a scurrilous woodcut lampoon of Caroline Matilda, printed in 1772, which “heralds the hygienic exclusion of the influence of women from political, public life, regardless of their rank, and their exile en masse to the seclusion of the domestic sphere” (p.88). The crude woodcut shows the queen on horseback, alongside a nurse holding her baby, and a male figure looking out of a window. The queen is construed as an “unnatural, sexually incontinent woman” (p.87) in the tradition of world turned upside down satire. The author suggests that the nurse represents the king, “left holding the baby” (p.89), the offspring of the queen’s affair with Johann Friedrich Struensee, the king’s doctor and prime minister. The threat to the royal bloodline at the centre of the print and the failure of masculine authority is embodied in the subversive and unruly woman. However, the king approved of Caroline’s wearing male attire, so contrary to a simple reading of the satire, the author suggests “the queen’s transvestism [is] a performative fall into masculinity responding to the king’s desire”, and a form of “sympathetic magic of mimesis” which constitutes the “body of the absolute king for him” (p.100–101). This reading questions and complicates the satire, based on traditional forms of unruly female representation and possible interpretations. However, the final example of consort portraiture is taken from an age of reproduction by means of photography. The narrative was reinvented for a new audience with irreconcilable binary gendered expectations determining its reception.

Alexandra of Denmark (1844–1925) married Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, in 1863. Her elaborate reception in the capital “created a topological phantasmagoria within which ancient ceremony and industrial modernity comingled” (p.113). The rise of the carte de visite form popularised the image of the consort but also enabled comparisons and imitations in its mass availability and reproducibility. Following this, “fashion and the photographic image” defined the image of the consort and made her “a visual commodity”, a development that has ultimately made the represented female body “simultaneously object and abject” (p.128). Though beyond the scope of the book, clear contemporary examples can be found in the consorts of the current British royal family. The book does not falter in its structured and thorough exploration. Each chapter contributes new material and builds on its central premise of change over several centuries. However, while the title is precise, the breadth of the subject may not be anticipated by the browser in a library or book shop. But the book is a rewarding study as part of the Northern Lights book series, and the portraits examined cannot be seen in isolation again.

Miriam Al Jamil is on the WSG committee, chairs the Burney Society UK, and is Fine Arts editor for BSECS Criticks online reviews. She has published on women travel writers, Horace Mann and his circle in Florence and Rome, on Frances Burney, and on Eleanor Coade. There will be a chapter on Coade in the forthcoming WSG book.