Following on from the arrival of WSG’s anniversary volume in paperback format, Louise Duckling introduces new books launched by two of its contributors: Sara Read and Tabitha Kenlon.

_________________________________________________________

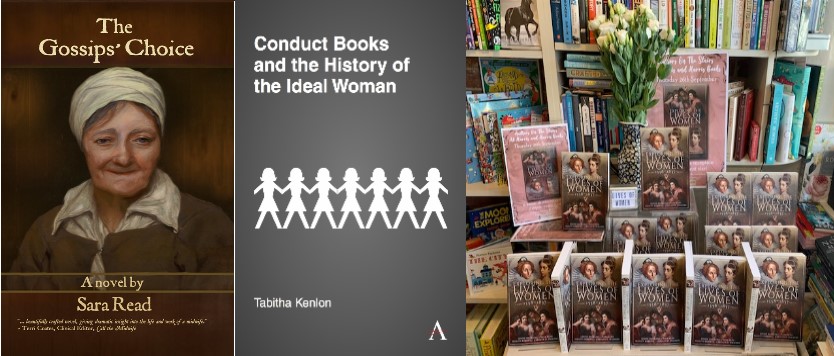

On an autumnal evening last September, a small crowd gathered at Harris & Harris Books in Clare, Suffolk, for one of its popular Author on the Stairs events. Gillian Williamson and I had been invited to talk about WSG’s anniversary book, Exploring the Lives of Women, 1558–1837, which had recently been released in paperback format.

As one of the book’s editors, I wanted to convey the scope and originality of our authors’ contributions in my talk. Therefore, I chose to address the question: why had so many of the women featured in the book been left out of the historical record? I considered how women’s history was constructed (and gendered) in Victorian biographical dictionaries, using our ‘bookend’ queens Elizabeth I and Victoria as opening case studies, before introducing some of the women whose lives are explored in our anniversary volume.

This approach led neatly into Gillian’s talk about her chapter on the Gentleman’s Magazine. Gillian eloquently described how the magazine constructed ideas of gender in the eighteenth century, specifically referencing the emergence of obituaries in its pages. The obituaries were used by Gillian (with some brilliant flashes of humour) to show how femininity was framed in the Gentleman’s Magazine, while also providing glimpses of a less-neatly gendered society.

There was an opportunity for the audience to ask questions and handle some of our original source material – an 1866 edition of a female biographical dictionary and an early volume of the Gentleman’s Magazine. We enjoyed lively discussion and hospitality, in the perfect setting of an independent bookshop. Reflecting on this evening, in such an intimate and sociable environment, it is clear we were very fortunate. For anyone releasing a book right now, any ‘in-person’ events or celebrations will have to wait. This is exactly the case for two of our book’s contributors, whose latest work has been published during the lockdown.

The first of these new books is by Dr Sara Read, who specialises in cultural and literary representations of women, reproduction and medicine in the early modern period. Sara played a pivotal role in the WSG book, serving as both co-editor and contributor, with her chapter focusing on The Countesse of Lincolnes Nurserie (1622) by Elizabeth Clinton and highlighting views around childcare and breastfeeding. In her latest work, Sara continues to draw upon this rich subject knowledge, while venturing into new territory: the genre of historical fiction.

In her excellent debut novel, The Gossips’ Choice, Sara has created an atmospheric world for her protagonist, the midwife Lucie Smith. The book has been described as a seventeenth-century version of ‘Call the Midwife’, as we follow Lucie’s cases during the plague year of 1665. It is a beautifully crafted and impeccably researched novel, drawing upon a wide range of historical sources. For example, some of the events in the book are inspired by A Complete Practice of Midwifery (1737), the memoir of midwife Sarah Stone. This approach provides authentic detail to a vividly imagined and compelling story.

The second new book release is by Dr Tabitha Kenlon. Tabitha’s research concentrates on eighteenth-century British novels, theatre, and conduct manuals. In Exploring the Lives of Women, Tabitha’s chapter provides a close reading of a single text, exposing the confused rhetoric in the cautionary pamphlet Advice to Unmarried Women (1791) written by an anonymous clergyman. Tabitha also contributed one of the two poems in our book, ‘Gretchen’s Answer’, which follows similar themes by exploring the consequences of “when society tells women how to think, how to act, how to feel” (Exploring, p. 98).

Tabitha’s first monograph continues this investigation. In Conduct Books and the History of the Ideal Woman, Tabitha shows how the longest-running war is the battle over how women should behave. This is an exceptional study, being the first of its kind to provide a trans-historical approach: expanding upon previous period-specific studies, Tabitha considers the persistence (or alteration) of the female ideal over six centuries. Tabitha’s brilliant close readings of a wide range of texts are superbly executed and entertaining, making the book highly accessible to the specialist or general reader. It is a powerful book, written with compassion and flashes of anger, in an elegant and witty prose.

Until we can all meet to celebrate, congratulations to Sara and Tabitha for producing two great books. Full reviews of both publications will appear on this website in the coming months: watch this space!

____________________________________________

The Gossips’ Choice by Sara Read is published by Wild Pressed Books for £12.

Conduct Books and the History of the Ideal Woman by Tabitha Kenlon is published by Anthem Press for £80 (hardback) and £25 (ebook). Please ask your institutional library to buy a copy. A 20% discount is available to WSG members.

Exploring the Lives of Women, 1558–1837, the anniversary book by WSG, is published by Pen & Sword Books for £19.99 (hardback), £12.99 (paperback) and £5.20 (ebook).

Please support your local independent booksellers if you can. Harris & Harris Books is currently offering a delivery service.